- בית

- אודותינו

- The Manifesto

-

-

- A State of Health

- A State of Security

- Gender Issues

- All Israelis are Mutually Responsible

- In Defense of the IDF

- Israel’s New Deal

- Judges in Israel

- Israel Among the Nations

- Land and State

- Prosperity and Dignity

- Responsibility, Vision, and Will

- The Democratic State

- The Israeli State

- The Nation-State of the Jewish People

- The Righteous State

- The Sovereign State

- The State of the Book - Education

- The State of the Jews

- The Sustainable State

- The Two-State Situation

- Yamma, Kedma, Tzafona, u’Negba

-

-

- הצטרפו

- לתרום

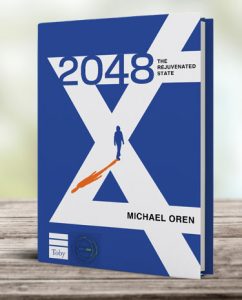

- BUY THE BOOK!

- בית

- אודותינו

- The Manifesto

-

-

- A State of Health

- A State of Security

- Gender Issues

- All Israelis are Mutually Responsible

- In Defense of the IDF

- Israel’s New Deal

- Judges in Israel

- Israel Among the Nations

- Land and State

- Prosperity and Dignity

- Responsibility, Vision, and Will

- The Democratic State

- The Israeli State

- The Nation-State of the Jewish People

- The Righteous State

- The Sovereign State

- The State of the Book - Education

- The State of the Jews

- The Sustainable State

- The Two-State Situation

- Yamma, Kedma, Tzafona, u’Negba

-

-

- הצטרפו

- לתרום

- BUY THE BOOK!

- בית

- אודותינו

- The Manifesto

-

-

- A State of Health

- A State of Security

- Gender Issues

- All Israelis are Mutually Responsible

- In Defense of the IDF

- Israel’s New Deal

- Judges in Israel

- Israel Among the Nations

- Land and State

- Prosperity and Dignity

- Responsibility, Vision, and Will

- The Democratic State

- The Israeli State

- The Nation-State of the Jewish People

- The Righteous State

- The Sovereign State

- The State of the Book - Education

- The State of the Jews

- The Sustainable State

- The Two-State Situation

- Yamma, Kedma, Tzafona, u’Negba

-

-

- הצטרפו

- לתרום

- BUY THE BOOK!

READ SECTIONS OF THE BOOK

תפריט

The State of Gender Equality

There has always been a question surrounding the title of Theodor Herzl’s foundational pamphlet, Der Judenstaat. Did the father of Zionism mean the State of the Jews or, rather, the Jewish State? A country with a majority Jewish population in which the Jews could determine their own fate or a nation that was intrinsically, indelibly, Jewish?

The Israel of 2048 must be both. By that date, the sizeable majority of the world’s Jews will live here, speak Hebrew, salute a Star of David flag, and follow the Jewish calendar. The problem arises only with the second interpretation. How Jewish does the state have to be in order to be not just a but the Jewish state? Who defines what is Jewish?

Unlike numerous democratic nation-states in the world—Denmark, for example, or Great Britain—Israel does not have an official religion. And yet, for all practical purposes, Orthodox Judaism and its institutions are recognized and even budgeted by the state and endowed with far-ranging powers. In life-cycle matters (birth, marriage, divorce, death), conversion, kashrut (kosher certification), and immigration these are monopolistic. So, too, is the Orthodox (Haredi) control over Jewish holy places, above all the Kotel. Most Ultra-Orthodox men do not work or serve in the army. Instead, they receive subsidies—paid for by Israeli taxes—to continue studying Torah.

The ramifications of this situation are massive. Though it helps preserve the Jewish people and its traditions, the status quo alienates a great many Israelis from Judaism and its state-sponsored establishment. It creates deepening rifts between Israel and the Diaspora and mitigates Israel’s ability to remain economically and technologically competitive. And it demoralizes and weakens the public which is required to shoulder the increasingly large burden, financial and military, of the Haredim.

Twenty years ago, as a fellow at a Zionist thinktank, I engaged in brisk debate over whether the state’s relationship with the Haredim posed an opportunity or an existential threat. I argued the latter. It seemed to me then, as it still does now, that the exponential expansion of a population that produced nothing materially but only drained the state would eventually bring it down. Israel would not be able to defend itself and, rather than continue to bear this outrageous burden, a great many Israelis would simply leave. This slow death, moreover, was funded by the state which paid Orthodox students in the religious schools (yeshivot) that left them utterly unprepared to work in the outside world and totally dependent on their rabbis and the government hand-outs they receive. “The situation is national suicide,” I said.

In response, some of my colleagues countered that the Haredim were not a threat but an opportunity—a highly intelligent and disciplined population which, if smartly and sensitively approached, could make tremendous contributions. Some of their predictions proved correct. More than half of Ultra-Orthodox men are currently employed and growing numbers serve in the IDF. But those statics are misleading. The Haredi birth rate still outstrips the growth of the Haredi workforce and the actual number of Haredi soldiers has been shown to be exaggerated. We are still en route to self-destruction.

That catastrophe must and can be averted. The first step, as mentioned above, is to insist that Haredi schools provide a core curriculum of English, science, and math. It means creating frameworks for teaching computer and engineering skills and incentivizing entrepreneurs to make Haredi-friendly workplaces. Alternative modes of national service, not just military, must be found in which the Haredim can serve the state—and their own communities—proudly.

None of this can be accomplished through coercion. Proposed legislation penalizing Haredim and their schools for draft-evasion will surely backfire and result in large-scale unrest and incarceration. Instead, the state must make an historic effort to engage Ultra-Orthodox leaders in a dialogue based on mutual respect and the assurance that the Jewish State has no desire to undermine the Haredi way of life but only to preserve it for future generations through integration into the mainstream.

A far more difficult task involves limiting the powers of the Chief Rabbinate. Once headed by more liberal National Religious rabbis, the institution is now dominated by the Haredim. It refuses to recognize the Jewishness of large numbers of Israeli and Diaspora Jews and rejects the conversions conducted by any rabbis, even the Orthodox, not included on a Haredi list. Unable to wed in Israel, couples of mixed religious backgrounds, as well as those unwilling to undergo a Rabbinate-approved ceremony, get married abroad. Still, divorce is only possible through the Rabbinate. So, too, are burial services and certification for kashrut, both of which have been accused of corruption.

The answer lies in breaking this monopoly and opening Jewish life in Israel to other streams, non-Haredi streams. Jewish couples should, for example, be able to choose which form of marriage ceremony—Orthodox, Conservative, Reform—they prefer, just as they can later chose which moyel, dayan, or any other religious functionary, including hevreh kaddisha (burial society). Though civil marriage should remain a goal, it must be approached with sensitivity to the Muslim, Druze, and Christian communities that will oppose it. Civil marriage exists nowhere in the Middle East.

Additionally, the state must set up a national process through which many tens of thousands of Israelis—most of them immigrants from the Former Soviet Union—can convert in a humane way that also respects Jewish law. It must create dignified spaces for those who do not convert but fall in the defense of the state to be buried with honor. The state must also ensure a proper place for non-Orthodox prayer at the Holy Sites. And the state must take back full control over the immigration process, reviving the original Law of Return and its criteria for determining who was a Jew: a person born of a Jewish mother and who remained a Jew, irrespective of how she or he practiced that Judaism.

None of this will be easy. The Haredi control over life-cycle events represents an enormous source of income for that community. That money, in turn, helps perpetuate the self-defeating system of Haredi dependence on welfare and the rabbis who keep them unskilled. Paternalistic though it may sound, ending the Rabbinate’s stranglehold will further compel the Haredim to seek secular education and well-paying work. It will aid them during national crises such as the Coronavirus, to which disproportionate number of uninformed and misguided Haredim fell. It will, moreover, help save the state from spiritual and financial breakdown.

This is not in any way to advocate for attempt to alter the Haredi lifestyle or to force anyone committee to it to be less observant. On the contrary, by assuring the sustainability of that community and the state on which it depends, these measures will guarantee a vibrant Haredi future. Having a sizeable section of its population dedicated to study and prayer, often at the price of self-imposed poverty, should be a point of pride for the Jewish State. But it must not come at the cost of the state’s very existence.

By working to make Israel more the State of the Jews, Israel will simultaneously make Israel a more Jewish state. It will strengthen itself economically, socially, militarily, and morally. A century after it first came to fruition, Herzl’s vision will be achieved.